Bernat Farrero – On Sales Leadership

Bernat Farrero on sales leadership:

I want to talk about sales leadership and to do so, let’s start with some of the values that define a leader:

Read MoreBernat Farrero on sales leadership:

I want to talk about sales leadership and to do so, let’s start with some of the values that define a leader:

Read MoreSimple solutions or “one fits all” policies are easy to market by populist governments but they are sometimes at the expense of certain sectors and their people. This time the affected party is innovation and value-added services, to a point that puts in jeopardy our (already weak) spot in the global competitiveness landscape. The new time and attendance law will kill innovation in Spain and Europe

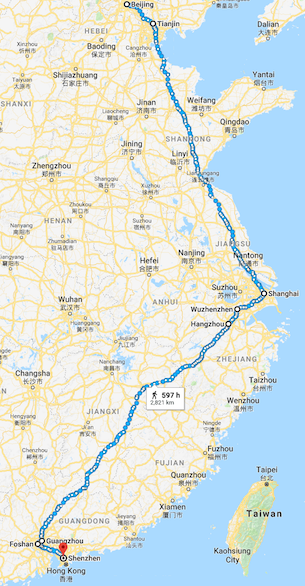

Read MoreThe last 24 days I’ve been wandering around different cities in China. My plan was to not have a plan. For once I wanted to travel alone and spend some time in different cities combining casual sightseeing, meeting people and making friends as diverse as possible. I wanted to talk, listen to people’s stories, lives, woes, concerns and successes. I wanted to meet businesses and entrepreneurs as well, also some potential suppliers for Camaloon. I was in Beijing, Tianjin, Shanghai, Wuzhen, Hangzhou, Guangzhou, Foshan, Shenzhen and finally Hong Kong.

My first realization was that I should have made this trip years ago. China takes a big part in our contemporary world, it has many resources and lots, lots of people. One cannot simply stay out of it and pretend to be globally oriented as I do!

Following you can read my personal impressions and experiences on my trip.

Language has been my biggest issue. I don’t talk Chinese and I realized the learning curve is so steep, even for the most basic words and sentences. Still, I have not given up yet. Translation apps, such as Google Translate, Microsoft translate and others made my life easier.

Chinese has completely different phonetics, 5 or 6 tones (Mandarin/Cantonese), their language is based on the combination of abstract ideas, where order and context matters a lot. Their writing is made up of thousands of symbols people memorize and combine (well, since the simplification Mao Zedong made on 1952 there are “only” 8.500 more simple characters compared to traditional writing). They have lots of sublanguages (some people call them dialects) but they share one unique writing.

Chinese people now start to learn English at school when they are 3 years old and they take it very seriously, English schools and academies are a huge industry and I met many people making a living directly or indirectly from it. That makes the typical entrance for foreigners, as there is a big shortage of native teachers almost everywhere.

However, most people I found could not say a word in English, they either were too shy to try, some just ran away, others looked for colleagues around who finally couldn’t say anything either. I’m not talking about isolated cases but that was the story of most of my street encounters with random people in mainland China.

However, people are open-minded, extremely hospitable, fun and have a great sense of humor. They are curious, and find interest in exchanging ideas and conversation with foreigners. Some locals who went abroad and came back complain that Chinese spoil foreigners too much (which differs from the discrimination they suffered when they lived in western countries).

In many aspects I felt closer to Chinese than to other European neighbors who are more rational, serious and formal.

The greatest migration movement that has ever taken place in our planet is that of over 500 million Chinese relocating from the countryside to the metropolis since the early 80’s until today. As birth rate in the countryside keeps being substantially higher than in cities, this movement will keep on for long.

All these newcomers to the cities share similar characteristics: They start from scratch in a highly paced environment, with lots of expectations and pressure, very few friends or known people and they have the mandate to learn, build a great career, make money, find wife/husband and come back every Spring for the Chinese New Year to show progress to their families. Almost 200 million people move every Spring to their hometowns.

Europe has a long tradition of migrations, and yet the magnitude of people who ever moved in or out ranges around 100 times lower than that of China.

Most people I met, specially young ones, felt lonely and paradoxically developed even stronger ties to their far away parents with whom they chat on Wechat everyday. For this reason I believe family life far from being weakened, it might have strengthened.

Family is probably the pillar in people’s life. Not a single person has not raised the issue of “what my parents want or say” even in our first conversations. The parents wills and desires are so strong in their children’s mind (even if they constantly complain about it) that sometimes can become overwhelming. For most young people I met, the top influencer was the mother, who generally is in charge of the child’s growth and education while the father spends more time out making money.

Parents will be taken care of by the child when they retire, so kids need to produce enough wealth on their careers and marriage. Either parents will eventually move to the cities, or their sons and daughters will return to their hometowns. Thus, marriage is key. It almost feels like the musical chairs, where everybody is looking for the perfect husband/wife (sometimes in purely economic sense) that will suit their parents.

This extremely materialistic approach (I hardly ever saw parents concerned about their children’s dreams or life vocation) probably comes from the very tough times that China experienced during Mao’s Cultural Revolution. In that time, where most kinds of businesses/trade were banned (among other things), many people actually starved to death. Some people told me the stories of how they were forced to eat tree roots to survive at that time.

Fortunately, that changed later on with Den Xiaoping’s reforms and it was the beginning of an aggressive planned capitalism that would transform society, first make people produce and save, and later push them to get trained and spend.

Compared to Europe, Chinese feel extremely comfortable with the establishment. They also follow patterns and trends like I’ve seen nowhere else. Except for the people in Hong Kong (who I found to be quite diverse), I could notice little differences between how people dressed, their styles, things they do and own, … Many people travel in groups, follow government rules, they get their info from the same censored media outlets and propaganda. And that’s ok. Most people do not have a VPN to access the outside world. Some don’t know about it, others say they don’t need it.

Me asking if they have ever thought of a different political or economical system for their country the unison answer is: no, why should they? When asking about controversial things being perpetuated by their government, most people either don’t know/believe them, or say that was long ago, or simply say that still makes the best option for them at the moment.

That is possibly one of the biggest differences with European civil society. To some extent people abandon individual ideas in pro of the collective. On the opposite side, European youth obsesses with indie, underground or bohemian movements all the time, as a trend itself.

If there is one thing I observed Chinese like, that is buying. They have malls everywhere, shops, street food bars, tea shops, restaurants, KTVs (individual karaokes), all kinds of attractions. Most people I met never cook at home, instead they order food or eat out.

Some people have one or two cell phones (most of them are iPhone) from which they continuously buy lots of things in Taobao or Meituan. Sometimes as we were having a conversation, they would feel hungry and order fruit or anything online (it didn’t matter it was Saturday almost midnight) and a delivery man would show up after 30 minutes with the items they ordered. They delivered to us all kinds of things at all kinds of places at a record speed.

The pace is so fast that you would not believe it until you experience it. People walk everywhere in huge crowds, almost not leaving free space or a slow lane in the street or subway. Almost all the people are eating or using the phone while walking, so they expect the flow to be continuous. You always feel pushed (sometimes literally) by the person behind you to move faster and never ever stop. I guess I was a turtle for my Chinese friends who would always ask me to go “quickly!”.

The idea of letting people out from places before getting in seems an abnormality. I’ve seen real battles by old ladies trying to get out from the train by pushing bellies around them. The streets and roads in Beijing and Shanghai are the most chaotic (and funny at the same time) thing I’ve seen. People drive in all directions on any road: eScooters (200€ electric scooters most people own), bikes (mostly from the super cheap OFO and Mobike app services), rickshaws, cars, buses, pedestrians, they all share and meet at the same space. Everybody (ab)uses the horn by default, not expecting anything from it, just as part of their driving. I saw a few crashes, but as none was serious, no one even stopped, they continued driving like nothing happened. I drove an eScooter a few days in Beijing and I felt inside a videogame. Great fun.

When you pay attention to what people actually do on their phones, you see they do all sorts of things (at once!). People watch TV (mostly shows or films), play videogames, chat with many people (sometimes work related), buy things online, all at the same time at a record speed. They do that while commuting (sometimes driving a bike or motorbike), while eating and sometimes while talking to you (something I came to hate). I felt an old guy asking people to focus on one thing.

While I was observing people, I was thinking of how this very idea of multitasking portraits China’s society. They are capable of doing so many things (sometimes at once). It makes sense to think that sometimes, statistically, some things will make a lot of sense. So many people doing so many things must trigger some sort of combinatorial darwinism that will produce the right things, sometimes new things. I came to realize that this iterative process (programmers call it brute force) is in fact a viable process for innovation.

If the official numbers are right we are in front of a highly populated (1,4B people) economy that grows at a 7% YoY (compared to the 1,6% of the US or 2,3% of EU).

Traditionally China comes from many centuries of a real autarchy (autonomous economy). They were able to produce all goods they needed in their vast and varied territory. It looks as if today 4 decades after their industrial revolution, they created enough middle class consumers so as to build their own huge internal consumer market again, which timely combined with a great consumerism appetite. Even in tourism, I could see how most visitors in all attractions and monuments were Chinese internal tourists.

Labor that used to be cheap and deregulated, it is now more expensive (around 500–600€ typical blue collar salary + 100–200€ insurance) and more closely regulated and controlled. Industrial production was once virtually free, and now is regulated and closely controlled by the government, leading to the closedown of many factories for environmental damage.

I could see so many government related job positions that seem to belong to a sort of country wide Keynesian policy. I found lots of people doing jobs of little importance (if not completely irrelevant). Such as traffic control, passport and security control, crowd organizers, door control everywhere and ticket offices at parks and all kinds of public spaces, etc.

I believe the main issues preventing more businesses from developing and foreign investment are legal uncertainty, kafkian bureaucracy, government opacity and corruption. Most foreign people who started companies there told me that the only chance to succeed is by having a partner who has ties with the government.

As I attended some entrepreneurship events, I could see a widely developing venture capital scene, corporate accelerators, venture builders, startup hubs and many entrepreneurs executing fast and strongly committed to get shit done.

I was surprised by how good most infrastructure works in China.

Even if it comes at the cost of privacy, you can always feel secure. Police is available everywhere, there are security cameras all over, even at the beach!

Public transportation is very modern, trains and buses come at very high frequency, the price is super cheap and the service is close to excellent.

Hospitals open 24 hours 7 days a week, you can book and even ask questions online.

Public toilets are available everywhere, they are clean and almost always have soap (but no tissues, you are supposed to bring it always with you).

Lots of taxis are available at a very low cost, sometimes even free (it was the case of some days in Shanghai). Competition is fierce and Didi (China’s Uber) lowered prices of the overall market. Everybody can drive a Didi, therefore everybody can afford taking it.

Bikes are available everywhere by two main companies: Mobike and OFO. They are so affordable and convenient that they replaced most people’s own bikes.

There are two state owned competing telcom companies operating in China since 1994. Their coverage is so massive and good that I hardly ever lost my signal anywhere. I paid 15€/month for unlimited everything and high-speed internet connection, and it delivered as promised.

However, China’s Internet should be called an intranet (no matter how big) instead. All traffic is carefully controlled by the government and highly censored. The Internet as we know it doesn’t exist. I could not access any Google service (from Gmail, Maps, Google Translate), Slack, Facebook, Youtube, Twitter, Whatsapp had a terrible performance and no images or video, I couldn’t access most of global or Spanish newspapers, … at least without a decent VPN (which slowed down the connection, and continuously self-disconnected). I used Nord VPN.

Most people I saw of all ages used iPhones to connect to the Internet. That’s probably why China is the biggest market for Apple phone sales (though many people told me that it would decline as Huawei, Oppo, Vivo, Xiaomi and other Chinese manufacturers were getting much better). I also realized that iPhone’s price was even higher than in Spain, making it a big investment for the lower Chinese purchasing power. China has the biggest Internet connected population, 730 million people. Following are India (460M users), and US (290M users).

Baidu is what most people use for search, maps and most of Google equivalent services. It only works in Chinese, so I could not make much use of it.

Tencent’s Wechat is the answer to Whatsapp and Facebook combined, but it has many more features. For example, Wechat is used to pay for all kinds of things. Most people don’t carry cash anymore, as they can use Wechat absolutely everywhere. A street tyre fixer, a parking controller, or even a beggar have QR codes you can scan to pay them. I saw how grandmas sent Wechat money to their grandsons. Every time I started counting my cash to pay in a restaurant my friends had already split the bill, paid and were waiting for me outside… But Wechat is also replacing email, as they feel more comfortable with instant synchronous answers. Most businesses (sales or customer service) will give you their Wechat contact to communicate with them. Interestingly, Wechat has its own application store of HTML based “mini-programs” that can access user IDs and Payment solutions. I used Meituan and OFO inside Wechat.

What Tencent is to social, Alibaba is to b2b and b2c ecommerce. Taobao, Tmall.com, Alibaba.com are widely used to buy things online (along with JD.com and a few others).

Alipay is Alibaba’s electronic bank solution similar to Wechat’s. Both Tencent and Alibaba filed for bank licenses some years ago and are already operating as full-scale banks in the whole country. They offer b2c and b2b loans and have developed their own social reputation scoring systems that the government is considering to officialize as public reputation systems (yes, scary).

They say China’s Internet is oligopolistic and concentrated in few mega-apps mainly the BAT (Baidu, Alibaba and Tencent) conglomerates, and only recently being matched by the second group TMD (Toutiao, Meituan-Dianping and Didi Chuxing). Toutiao is the most popular news site in China, Meituan is the leader for last mile delivery services and food discovery, and Didi is the leader in mobility. All these companies are constantly innovating, copying western products and services, and buying companies that add up to their offering and their huge customer base.

Most entrepreneurs I talked to were in some way digging into big data, machine learning and all applications of artificial intelligence. As the number of connected users is so huge and such few services accumulate so much user data and trends, combined with some relaxed privacy laws, I bet there is no better greenfield for AI experimentation in the world. I’m excited and afraid in equal parts of what can be accomplished by China on this field.

After centuries of positive trade balance for China against western countries (as they had enough resources and goods and had little interest in foreign products), the British started exporting Indian grown opium to China creating millions of addicts and serious consequences for China’s economy. When the emperor stopped British ships from trading opium and banned it, Great Britain, and later France, declared war to China. They totally smashed their unsophisticated armies, killed many and destroyed historical enclaves. That resulted in a humiliating treaty that would give unequal trade rights to the British and others and would grant the island of Hong Kong to the British empire forever. It wasn’t until 1997 that the colony was given back to China on the condition that its system would remain unchanged for the 50 years to come. Hence ‘One Country, Two Systems’.

Today HK is a melting pot of people from every part of the world and a majority of Cantonese Chinese. Fast, dynamic, open, free of entry without Visa, free access to uncensored Internet, most ordered public spaces, British right hand side lanes and car wheels. Mainland Chinese and Hongkongers regard each other with disdain. Hongkongers consider themselves more educated and open. Mainland Chinese historically consider them as sellouts, traitors or foreigner collaborators. HK is a tax heaven, financial capital in Asia, and also the center of operations for many companies who trade with China mainland, specially in the neighbor area of Guangdong, where the most important Chinese business trade show takes place: the Canton fair. You can cross the border with China on foot, through a bridge. I could see that many people does it everyday for work.

In HK many people speak English, many foreigners live there and it is the first time I see such amount of luxurious cars everywhere in the street. So many Tesla cars! A guy told me that around 15% of the inhabitants are millionaires. Of course the rest resign to live in the smallest apartments I’ve ever seen: smaller spaces than a parking spot where they’ve got kitchen, toilet and a room that sometimes share with different people.

Most things are very expensive, specially compared to China mainland. Transport is very efficient, some people never see sunlight as both their work and home buildings have direct access to subway. The subway card called Octopus also allows you to access and pay in most places from restaurants to supermarkets. An intricate net of tunnels and bridges allows you to cross the city without ever stepping a foot on the ground. Public and private spaces mix together: You go up some stairs to take a bridge, that later becomes a corridor, then it brings you to a bank hall, then a mall, then a roof park. It makes a very strange concept of urban space, that can become a challenge for orientation for people like me.

A country that has planned to lead the world and is committed to do so with an army of 1,4B productive workers (before blue collar and now highly trained) and consumers who are extremely pressured to learn and innovate, Europeans should feel called to work harder, to differentiate and join forces with them. We need more critical, strategic and creative thinking so as to compete and use more efficiently our smaller resources.

As competition gets more and more fierce, only powerful brands and very innovative concepts stand some chance against the oligopolistic conglomerates of the Chinese market. They have solutions (online products and services) for virtually everything: from cloud infrastructure, financial and human resources management, printing, mobility, … you name it.

We should waste no time and start placing China in our roadmaps!

You can check the pictures I took on my instagram. Check also Itnig podcast 27, where my friend Alexis Roig explains his experience running companies in China.

The first accelerator as we know it was Graham’s YC in 2005, followed by the franchise Techstars (2006), Seedcamp (2007), 500 Startups (2010), up to 1.600 currently in Crunchbase , along with incubators, seed funds, investment clubs, pitch forums, bootcamps, weekend hackathons, public and corporate incubators, … they are all different models that systematically look for winner teams and exchange a relatively low upfront investment, a set of services, a grid of mentors and other creative perks in exchange for equity stakes in their companies.

The profit of this model usually comes from returns on capital. One characteristic of equity based business models is that they yield results in the long term (generally 4–7 years). Thus, in practice, we’ve had virtually no time to see any of this models succeed just yet, even the few biggest ones have kept growing their expectations and none has yet consolidated and shown a real business success case (as accelerators, not as portfolio startups).

Conversely, we’ve seen many accelerators rise and fall, and they’ve shown less rigor and validation in their plans and results than the startups they try to accelerate. Plus, most accelerators have required a lot of cash to sustain their team structures and the startup investments, no matter how low they are. And their ordinary income is usually limited or zero.

How can we industrialize the hunt for opportunities that have the statistical probability of finding a needle in a haystack?

I learned that opportunities show up while looking for something else. Most business success stories have a big part of that, they are based on a series of random events in time combined of course with commitment, vision and great effort. And yet, none of these stories are repeatable. Most stories require different learning paths, resources, timeframes, influences, etc. to reach success. To give real support to that, we would need to create a tailored suit for each company.

But accelerators keep promising their investors that they are better-off in finding opportunities systematically, and defining one-fits-all programs for N number of companies, with N number of office hours, N mentors, N resources per startup, and so on. But the question remains, are they really creating value or systematically praying to find a winner team in each batch?

We could argue that, if you are the best of the best, that is: you have rockstar partners full-time involved in the screenings, top-notch mentors such as Zuckerberg, Houston or Hoffman influencing the program, you are guaranteed future investment no matter what you do, you have a real network of first corporate clients, potential partners and suppliers.

You would be creating a closed economy capable of triggering self-fulfilling prophecies. But you should still cope with the intensity and the rhythm, digest applications from the best entrepreneurs in the world in very very big numbers, and keep doing that forever, if you are to maintain your program running. Very few accelerators fit in that description, maybe only Y-combinator. Even other popular ones like 500 Startups are moving up to more advanced stages of the investment lifecycle, and others are focusing on doing “innovation consultancy” to corporations (which is an entirely different business model).

For equity to be revalued and returned, the most usual case is selling or IPO. Other possibilities for selling stock are very hard, and usually out of control. So in the business plan of any accelerator, it is hard to add lines of income (from returns on equity) at any point in time. The only predictable cash-in is that paid by investors.

We should add up all the chaos from a startup lifetime: founder fights, many financial rounds, creative VC contracts, expensive executives, and other painful but unavoidable woes in each startup life. At some point the once shiny presence in the cap table has evolved to pure insignificance.

So there’s no step in this chain which I wouldn’t tag as HARD or highly unlikely:

The conclusion is that accelerators have even less chances of success than the startups they accelerate.

Pitch screenings usually are the only way to digest all the deal flow of startups in a finite amount of time. But, if you pay attention to the process, you realize that it has more to do with theater playing and story telling than scientific business facts.

It is difficult to make good choices based on such short interactions, but at the same time it is the only way to fit 10, 20 or up to 80 candidates in a program (out of 100, 200 or 1000).

Another at least questionable thing are the mentor grids. Every accelerator has their own mentor grid, many of them are shared between different accelerators. In some cases, mentors are self-assigned, and usually they are paid in equity.

In the real world, a good entrepreneur will have to fight to search and gain his/her own allies. The best mentor is the one that has valuable knowledge for the particular sector or activity of the startup and creates a long term love relationship with the entrepreneur and the project. The best mentor is convinced to risk his/her own money to invest in the company. The best mentor has something to loose when he/she gives advise.

In some cases, mentors, or even accelerator managers don’t have direct experience scaling real world businesses, and seek to learn themselves from startups and not otherwise. This makes it even more difficult to create the right abstraction for the acceleration program to work, not to mention to plan for its industrialization.

We keep hearing the songs about “unicorn” startups that combined are worth more than most European countries GDP. Who can blame contenders who want to replicate that in their backyard? But often, the real risk involved is closer to pure gambling.

Don’t get me wrong, accelerators are great for society and economy. Most entrepreneurs don’t know where to start from, and any structured help can put them up on their feet. And they are not stupid, if they decide to be accelerated it’s because they are getting value from it… their business will be the sequence of their decisions after all. One different thing though is wether accelerators are capable of capturing value for themselves. At least most of them proved the opposite.

They combine so many highly unlikely and unpredictable success factors that in practice they are almost impossible to plan and execute.

Top ones aside, the future of accelerators will be more tied to the government (either directly or through public subsidies), as they do have a social benefit and it is fair to be so, or they will be tied to corporations as purely subsidized think tanks (hopefully entrepreneurs will understand the real implications of that), or they will become highly specialized by sectors.

Many existing ones will evolve to either venture funds (post-traction investment funds) or venture builders (responsible for the entire execution of the business).

At itnig we start one or two companies each year from scratch with teams who have previously worked with us in some way, so we know how they think and execute. We don’t do screenings, instead we analyze markets.

We don’t have a fixed program, instead we accept direct responsibility to scale each business as any other founder. We don’t have a short-term exit plan, but we keep involved and working in the business for as long as it requires.

Our goal is to grow the business as much as possible and execute its vision, it is not to solely to raise new financial rounds. Our services are not based on equity, they are paid by startups at their cost, according to the needs of each startup. We strive to keep always a very lean and flexible common structure (outsourced if necessarily), making sure it never becomes a yoke to anyone, and we are 100% transparent about our ordinary P&L with the rest of the founders, so there is no room for conflicts of interest.

Of course a venture builder has many cons too, as it is less diversified and it involves much bigger risk per investment, but that would be the subject of another post.

At itnig we put all our focus in finding the right talent to work in our startups, part of this talent will be our cofounders in our future ventures.

Feel free to check out our website, participate in any of our events, or learn about our open positions.

The other day a friend was arguing why he would never accept money from an investor to start a company. That would make him responsible and he would feel stressed by having to report to that future shareholder, specially when things go south. He was better off being “free”, doing always “what he really wants” and “not having to answer to anyone” for his actions.

Unfortunately, that is a generally spread idea that prevents even greater initiatives from developing all the time. To me that is the fear of commitment.

We humans work better collaborating together, sharing and compensating strengths and weaknesses. In order to do so, we build relationships based on trust, honesty and respect. That has always been the relationship I tried to build with my shareholders. I’ve shared with them the opportunities and also the uncertainties and the risk. Those who wanted and properly understood them, have decided to join me, compromise some money and bet for the best.

However,

Thus, I keep committing all the time and love to do so. I commit with my employees, my shareholders, my clients, my suppliers, … but also with my girlfriend, my family and friends. What’s so wrong about committing? Commitments are not a burden, but the tangible consequence of our own decisions.

Beyond our words, it is our commitment and our consequent action what truly defines who we are and how we will be remembered.